- Home

- Barry Knister

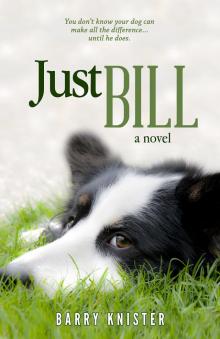

Just Bill

Just Bill Read online

JUST BILL

Copyright © 2012, 2017 Barry Knister

All rights reserved. Except as permitted under the U.S. Copyright Act of 1976, no part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, or stored in a database or retrieval system, without prior written permission of the publisher.

This book is a work of fiction. The characters, incidents, and dialogue are drawn from the author’s imagination and are not to be construed as real. Any resemblance to actual events or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental.

Published by Asher

an imprint of BHC Press

Library of Congress Control Number:

2017940067

ISBN: 978-1-946848-13-0

Also available in softcover and ebook

Softcover ISBN: 978-1-946848-73-4

Visit the publisher at:

www.bhcpress.com

The Dating Service

THE BRENDA CONTAY NOVELS

The Anything Goes Girl

Deep North

Godsend

FOR BARBARA

Back in the animal shelter, he resumes a life of sordid, empty days. Dogs come and go. Filling the hours, a welter of sensory overload gives way to boredom. Harsh Florida sun hangs all day in front of his crate; at night, shards of lightning stab down through the skylight. Being brought back this way, he has trouble eating. In four days, he loses two pounds.

Then, on the fifth day he is let out in the morning with others, in the fenced yard. Hot and humid, the air is something to push through. By noon the sky has darkened, and by two the trees bordering the adjacent barns clatter and sway. Dust whips through the yard. A plastic bucket flies against the stucco wall, then a lawn chair. One of the animal-shelter staff is now crossing from the sheds where public works equipment is stored. Hunched and facing away, she is holding on to her broad Smokey-the-bear hat. As she nears the gate, her phone rings. She unclips it from her belt and starts talking, holding her hat, working to open the gate. The hat blows off. Still talking, she turns and chases it, back toward the sheds. The hat whips and bounces.

The gate bangs open.

—Come on.

The German shepherd is already outside. Skillfully mastering his injured leg, he starts loping away. It’s wrong, the dog thinks, watching. Running away is a bad thing you get scolded for, even hit on the nose with newspaper. He watches other dogs scuttle out, the woman still chasing her hat.

He chooses, and runs. Digging his hindquarters, racing for the gate he bangs a Weimaraner—and then he’s out, racing to catch the shepherd. It’s easy to do, the shepherd hobbled. But he is now loping in a steady, altered three-legged canter, clear of purpose. The dog reaches him. The message coming from the shepherd has to do with distance, the need to leave the shelter behind. In back he hears shouting, faint in the wind. Ahead, a fallen palm frond whisks across the road. In seconds they reach the highway. They run west, side by side on the shoulder.

—Just run, the shepherd signals. —Don’t look back. Run.

They do, together. He paces himself to match the slower dog. Everything now is wind. Everywhere leaves and torn seeds fly at them—they’re running directly into the first hours of a storm that has brewed for days in the Caribbean. Now rain falls in sheets. It doesn’t start small, there’s no light pattering first, no slow build. It’s thrown, pitched and dumped on all beneath. On the right the hot asphalt steams. Traffic barrels past, lashing the two dogs with waves. Horns bray. Headlights and fog lamps seem to charge all at once through the rain curtain, whipping past.

How far? A mile? All there is to know lives in his big legs and chest, energy and instinct. And the shepherd. Would he have run without him? Either way he has made another choice on another road, this one in Florida, in hurricane season, dodging a limb torn from a cabbage palm.

And in the clatter and steam of it, the slashing spray of passing cars—something registers. He knows this place. In his brain, narrow but deep in terms of sound and smell, he is certain. Ahead, lights are flashing. Some cars have pulled off the road. Nearing them, he leads the shepherd, picking up more clearly the scent and certainty that he is right.

—This is good, he barks. —On the other side. I know what this is.

No time or need to think. He cuts right and dashes over asphalt. This is where he lives, this is the mister and missus, the pool and rugs, the bed to be under in storms like this. Tires skid, a horn blows. Still it blares. On the wide median he stops. The shepherd isn’t with him. He whines and barks, a surprise even to those hard pressed to get where they need to be in such a storm. For a moment, distracted from worry about their cars and houses they point at him. Slowing, they inch along the right lane as others race in the left, many talking on cell phones, telling one more detail from this squall-soaked day on Davis Boulevard, telling the person on the other end about some crazy big dog out on the median, maybe a Lab, a big one barking his damn head off in all this weather.

If this afternoon the dog’s owner were traveling in one of the passing cars, deafened by drumming on roof and hood and slowed by the storm, so that he all at once saw what was there, on the median, it would break his heart. With furious drivers honking and yelling, he would stop his car, get out and call to his dog.

But he isn’t there. And what’s happening on Davis Boulevard is months away. Right now it’s late spring, with things as they always are.

It’s not your fault, it’s my fault. Don’t you see, Hotsie? God, out buying pots…”

On the grass behind the Gilmores’ pool enclosure, four dogs watch as Glenda Gilmore again breaks down. She’s on the couch in her living room, dressed in a black leotard and shorts. “My fault, my fault—” She shakes her head, pounds her knees. As he has for twenty minutes, Hotspur sits opposite, bolt upright on Cliff Gilmore’s BarcaLounger. His black coat glistens under track lighting, chest and muzzle pure white. As if to console Glenda, he raises a paw.

—She keeps talking about a sale, Emma says. —She was shopping when it happened.

—Sale?

Emma, a miniature poodle, glances at Chiffon lying next to her on the grass. Chiffon is a bichon frise. The look of separation anxiety on her face comes any time something disturbs her lapdog life. Emma turns back. —More tears, she says. —‘All my fault, should have been here.’

—Fault?

The sun is setting. Again the poodle turns, this time to look out on the golf course. Everything is just now turning pink, the lawn and white sand traps, the blank row of condos to the west. Late-afternoon players are all in now, the last golf cart back in the shed. Here and there the eleventh fairway is traced by wide tire tracks. On the far side, the coming of darkness is marked by the bone-white trunks of melaleuca trees. Birdcalls in the upper branches mingle with Glenda Gilmore’s crying. Ditzy, Emma thinks. She doesn’t know what it means, but often hears the word used with Glenda Gilmore. And floozy.

—She is a good missus.

For emphasis, Bill lowers his big body to the grass. He settles with paws extended and head erect, intent on the Gilmore living room. —She likes to walk. She likes playing Frisbee. She goes with her mister when he takes Hotspur to the beach. Glenda is a good missus.

Emma looks again to the open doorwall. Still seated and motionless, Hotspur has not taken his eyes off the crying woman. He can’t, of course, he’s a border collie. But Glenda Gilmore won’t see it that way. To her, Hotspur’s unwavering gaze means he’s paying attention, being sympathetic. That’s why she loves him so much tonight, confiding in him, apologizing, confessing. They’re more or less all like that, even Emma’s own mistress, Madame.

—Stop crying, Luger growls. —People get old, people die. Geddagrip.

The toy schna

uzer on Emma’s left shakes his head free of gnats. Geddagrip is something his mister says all the time.

—I feel sorry, Chiffon whines. —Crying is unhappy. When my missus cries, I cry too. She’s old, she says so. Her mister died and she cries. It’s sad.

—Feel sorry for Hotspur, Emma says. —He has to keep sitting there.

—Hotsie is a dog.

—So are you.

—No. I’m Babycakes. Snookums. Love muffin.

She’s old, it’s sad. But “old” does not apply to Glenda Gilmore. Not at Donegal Golf and Country Club. Before she married Cliff and came here, she was a Lands’ End model. That’s why the other club wives call her a floozy.

Rising now with the Kleenex box, she disappears behind half-closed vertical blinds. At last Hotspur is free to look out. He’s heard and smelled the other dogs all this time and wants to run out through the open doorwall. But he must now weigh this impulse against his sense of duty. It’s bred into him, like his border-collie stare. Finally deciding, he hops down and trots after his mistress.

—People die, Luger says again. —They live, they die.

—You told us, Emma says.

—Work hard, play hard, die. No crying.

—You told us.

—Work hard, play hard—

She barks at him. The single, harsh report echoes out into the darkness. Silenced, after a moment the schnauzer takes a breath and lets it out. He rises on his haunches.

—Time for the walk, he says. —Night. The walk, the news, then sleep.

He turns and trots along the brick path at the back of the pool cage. Luger may or may not stop to tell the three Yorkshire terriers about Cliff Gilmore. It depends on whether the Dog speech is still going on in his well-groomed head. Once under way the speeches are hard to stop, something like the prey drive in certain breeds.

—I’m going too.

Rising, Emma stretches luxuriously. Chiffon also stands. She hates walking alone, and this is also true of her mistress. Like Emma, the bichon was raised from puppyhood by one person. Few would believe how closely such dogs come to resemble their owners.

—What about you?

Bill shakes his head. He is standing again, still intent on the open doorwall. Compared to the other dogs, he is huge.

She turns and begins walking along the brick path. Buddies. That’s the human word for Bill and Hotspur. Chiffon is not a buddy, but she now catches up and trots alongside.

Bill watches them follow the narrow footpath. From the back they look like littermates, but two dogs could not be more different. Chiffon seems never to have had an actual thought, but Emma has real intelligence. And she knows words, lots of them. Hotspur is smart, too, but border-collie smart. That means something else.

He turns back to the Gilmores’ pool cage, hoping the collie will come out. The open doorwall reveals a comfortable interior. Like the house he lives in, it has high ceilings. There are colorful pictures on the walls, furniture and area rugs. Being tall, Bill can see to the front foyer. His long legs and deep chest, his big head and serious face all make him an oddity at Donegal. With few exceptions, the dogs here are small breeds, easily carried on planes or crated in cars.

Again the Gilmore woman appears in the opening. She is tall, with broad shoulders and short red hair. No longer crying, she reaches up and the doorwall rumbles closed. Vertical blinds begin tracking across the glass.

Resigned, Bill flexes long, solid legs, then stretches. Half Labrador retriever, he is black with short hair. His muzzle is longer than those of purebreds, and his height leads people to speculate on his parentage. His broad chest has a white streak, giving him what his missus calls a well-dressed look.

He turns away and regards the jungle rough on the far side of the fairway. Against the deepening night sky it looks thick and black. Maybe the Gilmore missus will feel better when she takes Hotspur for his walk. That’s something everyone with a dog has to do. Work, play, knee or hip pain, parties, brunch, church—no matter what, they have to walk the dog. Bill’s mister sometimes sees Glenda out with the collie. The next time this happens, he will tell her he is sorry.

Bill begins trotting along the brick path in the opposite direction taken by the others. All the houses here have pools and spas protected by screen cages. He passes two with doors and windows already sealed behind storm shutters. Come the rain and sultry weather of hurricane season, half the houses at Donegal will look like that.

Sorry. People stopping to talk use the word often at Donegal. Bill’s mister always takes off his cap, holding it behind his back as the other person tells about someone who’s died, or gone to assisted living. Or just had or is about to have surgery. Restaurants, church, scramble tournaments, shotgun starts, owner assessment fees—understanding none of it, Bill waits patiently.

He nears the Telecoms’ big house. That’s what Madame calls them, Emma’s missus. Madame is one of the original residents at Donegal, and she knows telecom stock is how the family made their money. Inside, both white-haired Telecoms are on their red couch, watching TV. They each hold a dachshund, and all four are watching the screen.

Bill continues along the path. The birds have stopped, but insects are now diving and buzzing around his ears. Although they’re floppy they stand high on his head, giving him a vigilant look. It makes some people nervous. Along with being half Labrador, there is German shepherd in him. A quarter of Bill is Great Dane.

Vigilant, yes, but not fierce. Bill is what’s called a soft dog. He likes the dachshunds and other small dogs, letting them bounce around and sniff him. Mrs. Telecom loves Mozart, and that explains her dogs’ names, Wolfi and Stanzi. Her husband takes them with him when he plays golf. They are a fixture at Donegal, and a source of envy among other dogs. How can you not feel envy, seeing them seated side by side on a platform between golf bags, their small, proud heads raised as the cart trundles over the course? Before hurricane season they fly north, in a satchel placed under the missus’ seat. When they get there, the car is waiting, shipped in a truck.

AS HE NEARS the Vinyl house, Bill trots faster. His hearing grows precise, ears more erect. He was saved by his mister, and there is nothing he can ask that Bill won’t do. Reaching the screen cage, he sees the man inside, on a chaise. It fills the dog with longing. The reading lamp is on, Vinyl stretched out next to the pool reading a magazine. A sound comes from Bill’s throat, something between a whine and a yodel. It’s impossible not to love what he sees, impossible not to want to be with the man—lying, sitting, walking—anywhere at all.

The mister lowers the latest issue of Time. “Old Bill, old scout—”

The cage’s screened door was designed to open out, but Vinyl has reversed it. Bill places his left paw on the frame, and shoves. Quickly he noses in and begins slipping through. Door and frame rub his sides, and sometimes his tail gets banged—but not tonight. The door claps shut as he trots over. The mister is sitting up, ready to greet him.

“Good old Bill, what’ve you been up to?” Using both hands, Vinyl begins scratching the dog’s neck. Now he scratches behind the ears. I love it, Bill thinks, eyes closed. Always the same, every time. “You digging anywhere? Don’t be digging, Bill, no more of that, right? We agreed, didn’t we?”

Digging. Of course not, Bill thinks. Never. Eyes closed, barely able to stand, he feels transported. This perhaps is the best, to be greeted this way and scratched in the best places as the mister speaks to you and you alone.

Vinyl likes it, too. At such times he often thinks about the dog’s name. The Depression-era song “Bill” had still been popular in his boyhood during the war. Fifty years later, having done well in vinyl siding, he sold his business and bought a place in Florida, then one on a lake in Michigan. And two years later, up in Michigan sometime after eight in the morning, walking as he did every day before breakfast along a tree-canopied dirt road, he had glanced back. Trailing him by fifty feet was a long-legged, skinny stray. “A bag of bones” is how he later put it.

For half a mile this went on, until Vinyl at last stopped and waited. Sick with parasites and not yet a year old, the dog was already big. In one of those moments that alter every day to follow, Vinyl put out his hand. The stray touched it with his nose. They had walked home, where Vinyl fed him against the protests of his wife.

The glass slider opens. With the scratching still in progress, Bill looks over as the missus steps out. She dislikes him less now, but that first day she saw him as a nuisance. What if it’s sick? she called from the house as they came up the drive. What if it’s dangerous? It’s a mutt, a mongrel. What are you thinking? No papers, no breeder. We’re retired, we don’t need the aggravation. Vinyl didn’t answer. At the door, he knelt on the walk and looked in Bill’s eyes. He opened his mouth to see the teeth, felt along the ribs, then placed his fingers in the gaps between. He’s letting me touch him all over, Vinyl said. He trusts me. They do the choosing, just like women. But the missus had already gone inside. Still kneeling, the man cupped the dog’s face. You’re a hobo, he said. A Depression dog. Your name is Bill.

“What a nice night,” the missus says. “Want some tea?”

“Sounds good.”

She is again holding the thing, looking down at it in her arms. For days she’s been doing this. Wrapped in a receiving blanket like a real baby, it has a shiny face. The eyes blink as the missus rocks, and now it makes a sound something like a cat. “What do you think, Bill? This is Jeremy. You’ll meet the real Jeremy tomorrow. Yes you will, just as cute as they come.”

She reaches down and holds it in front of him. It smells like the shower curtain. He looks up and sees the missus is smiling. She straightens and goes inside. “It’s something she read,” Vinyl says, still scratching. “She thinks you might be jealous of the baby, so she’s getting you ready with a doll. Her middle name is worry.”

The Anything Goes Girl (A Brenda Contay Novel Of Suspense Book 1)

The Anything Goes Girl (A Brenda Contay Novel Of Suspense Book 1) Deep North (A Brenda Contay Novel Of Suspense Book 2)

Deep North (A Brenda Contay Novel Of Suspense Book 2) Godsend

Godsend Just Bill

Just Bill